A new Star Trek RPG is in the works! Modiphius Entertainment has the license, as they announced recently on their website. I interviewed Modiphius’s publishing director, Chris Birch, for Gnome Stew. Here’s a link!

gnome stew

Ghostbusters: The Next Generation

This is post number 14 in the series “31 Days of Ghostbusters,” a celebration of the franchise’s return to the big screen.

(Today’s post also appears on Gnome Stew, the best damn gaming website anywhere. I’m posting it here for continuity, but I suggest you read it on Gnome Stew. It’s prettier there.

The Ghostbusters RPG (which we talked about recently) may be dearly departed, but it lives on in spirit. Elements from Ghostbusters have made their way into later games, either in the form of game mechanics, philosophy, sense of humor, or subject matter.

Here are some of the games that were either inspired by Ghostbusters or that enable you to bring similar themes and activities to your gaming table. In some, you bust the ghosts; in the others, you ARE the ghost. Please note that we can’t cover every ghostly game, so if we didn’t mention your favorite, please sing its praises in the comments!

Ghost-Busting Games

InSpectres

“Battle the forces of darkness and try to keep your business afloat in a world of ghosts, demons, vampires and IRS agents.” – Memento Mori Theatricks, 2002

The introduction to InSpectres tells us that the game is loosely based on two things: Ghostbusters and reality TV shows. Like Ghostbusters, InSpectres is a rules-light design: a character has four skills and one unique talent; everything is driven by a few 6-sided dice; and the whole shebang is contained in one 80-page digest-sized book. It’s also got ID badge character sheets and “Cool dice.” The reality TV angle comes in with the game’s use of Confessionals, which are mini-scenes in which one player gets a moment to address the “camera” individually. One of my favorite things about this game (which I’ve repurposed for my Ghostbusters campaign) is the franchise dice concept, providing a pool of dice that the group can earn and any individual can spend.

Green’s Guide to Ghosts

“So you think strapping a nuclear reactor to your back and waving a proton-thingamahoochie around makes you a ghost hunter? Think again!” – 12 to Midnight, 2005

Green’s Guide to Ghosts is a ghost-hunting setting book for Savage Worlds. (A version for d20 is available, too.) The book is presented and narrated by Jackson Green, a professional ghost hunter who tells it like it is. Green’s Guide aims for coverage that is thorough rather than minimalist (not that this is a problem, considering Savage Worlds isn’t overly complicated), and offers a comprehensive selection of ghost hunting rules, equipment, and character abilities. One unique thing about Green’s Guide to Ghosts is its use of seances; in addition to providing rules for holding one in-game, Green’s Guide also gives the GM advice for staging seance scenes in real life. I’m also fond of the book’s comprehensive lexicon of paranormal terms, from ABE to Zener Cards.

vs. Ghosts

“Whom do you call when things go bump in the night? Ghost hunting with vs. Ghosts will make you feel good!” – Fat Goblin Games, 2016

This is by far the newest game in the list, because it came out just this week! vs. Ghosts is a rules-lite ghosthunting game featuring five attributes, a simple character sheet, and a Ghostmaster. Sounds like just what we’re looking for! Based on vs. Monsters—an even shorter product created as part of the 24 Hour RPG project—vs. Ghosts also features ghosthunting gear, ghost rules, and a well-illustrated section of sample ghosts.

You’re-The-Ghost Games

Wraith: The Oblivion

“Do you listen to the voice inside your head telling you to just let go? Or do you still fight, still love, still feel the passion that won’t let you rest?” – White Wolf, 1994

The fourth game in White Wolf’s World of Darkness, Wraith let players cross over to the other side and play as ghosts. Like the other World of Darkness games, Wraith provided character choices that encompass different types of fictional representations, so your ghost might the kind who can possess people, or haunt a location, or manifest physically, or enter the dreams of mortals. A unique element of Wraith is the fact that each character has a Shadow, which is the dark side of that character, controlled by another player!

Orpheus

“What if you could die and return to your body, to live again?” – White Wolf, 2003

Orpheus was another World of Darkness game, published after Wraith, though the Orpheus line was designed as a limited release of six books. Player characters in Orpheus could be ghosts, or they could instead be living people with the ability to enter the spirit world. Players in this setting use their spectral abilities (which are reminiscent of those in Wraith) to investigate and confront ghostly threats.

Geist: The Sin-Eaters

“Death is a door. You are the one with the key.” – White Wolf, 2009

(OK, sure, this section is looking pretty well dominated by White Wolf Games. What can I say—they clearly have a leaning in that direction! And so do at least a few Gnomes…Martin wrote a preview of Geist back in the day.)

After White Wolf rebooted their World of Darkness in 2004, they published another take on the ghostly experience called Geist: The Sin-Eaters. Players are not exactly ghosts; they are the titular Sin-Eaters, and each Sin-Eater is spiritually tied to a ghostly being called a geist (an aspect of death). I like the fact that in Geist your character’s cause of death has a mechanical effect, such as the type of geist that’s drawn to you, and the kind of powers you can use. Like its older brothers, Geist had powers aplenty, plus atmospheric details like fetters and ectoplasm and haunts. Geist was a limited-run series, consisting of the core book plus a Book of the Dead.

Beyond

“Can you resolve whatever holds you back before Entropy steals your name?” – Stew Wilson, 2013

The record for “ghostly minimalism” (surely that’s a thing?) has a new champion in the form of Beyond, a two-page pay-what-you-want RPG. (And one of the pages is the character sheet!) As you might expect out of such a length, Beyond is strongly story focused. The game rotates the role of GM (called “Entropy”) between players, changing every scene. The to-the-point rules include a dice pool of red, white, and blue six-siders plus a list of simple but classic ghostly powers. There’s not much story guidance here, but if you and your players like taking a basic idea and improvising off of it, this game is a spooky place to start. (Er, spooky in a good way.) And if two pages is just too much reading for you, the designer also offers a lite version of the game called Unfinished, weighing in at 150 words.

Have you played any of these ghostly games? Or do you have others to recommend? Are you running a new (or old) Ghostbusters inspired game using another system? Let us know below!

A History of the Ghostbusters Roleplaying Game

This is post number 6 in the series “31 Days of Ghostbusters,” a celebration of the franchise’s return to the big screen.

Today’s post also appears on Gnome Stew, the best damn gaming website anywhere. I’m posting it here for continuity, but I suggest you read it on Gnome Stew. It’s prettier there.

Ghostbusters Begins: A History of the Ghostbusters Roleplaying Game

A Brief Overview of The Ghostbusters RPG

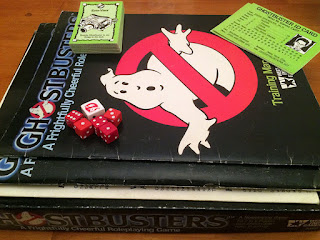

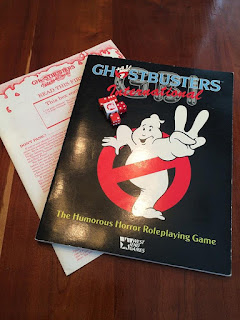

The Ghostbusters RPG was released in 1986, just about midway between the theatrical releases of the two original movies. The game boasts an amazing pedigree, having been designed by Chaosium (the makers of Call of Cthulhu, first released five years earlier) and developed by West End Games (the creators of Paranoia in 1984). Long-time gamers will probably recognize some of the names involved in the game’s initial launch: Sandy Petersen, Lynn Willis, Greg Stafford, Ken Rolston, Martin Wixted, Paul Murphy, and Greg Costikyan.

Ghostbusters shipped in a box (retro, right?) and contained a Training Manual, Operations Manual, How To Play file, 6 dice, equipment cards, and Ghostbuster ID cards. The 24-page Training Manual served as a player’s guide, presenting character creation, basic rules, and a primer on ghosts. Inside the beefier 64-page Operations Manual you’d find material for the GM (the Ghostmaster, of course), including rules for creating ghosts, conducting scientific research, and establishing a ghost-busting franchise, in addition to GM tips, three adventures, 21 adventure ideas, a random adventure generator, and a bunch of useful non-player characters. The How To Play file provided a quick rules summary, adventure maps, and some fun forms such as a Franchise Contract and a Release From Damages form.

How It Plays

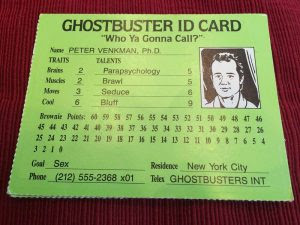

In Ghostbusters, players take the roles of either the cast of the movie (using the provided ID cards) or their own custom paranormal exterminators. The game’s background establishes a narrative framework for the latter in describing a parent company, Ghostbusters International, that sells franchise rights to wanna-be Ghostbusters in different cities. (Peter Venkman even mentioned this possibility in the first movie.)

Besides being a game that lets you become a Ghostbuster, the best thing about Ghostbusters was its elegant simplicity. This game has no speed or movement rates, no ranges, no advantages or disadvantages. Here are the basics of the Ghostbusters rules:

- You have four Traits and four matching Talents. Traits are attributes, including Brains, Cool, Moves, and Muscle. Talents can be anything that could be governed by the Trait, such as Parapsychology, Getting a Date, Climbing, and Breaking Down Doors.

- You roll a number of 6-sided dice equal to your Trait rating (which is typically between 1 and 5), adding 3 dice if your Talent applies.

- One of the dice you roll is a special Ghost Die, with the Ghostbusters logo on the 6. If a player rolls a ghost, something bad (and probably funny) happens.

That’s most of what you need to know to play the game! Check out the tiny character sheet!

We’ve already covered most of the details on it. The other pertinent bits are Brownie Points and Goal. Brownie Points are the Ghostbusters version of experience points, which you can spend to enhance dice rolls, reduce story penalties, and (more rarely) upgrade Traits. Characters earn Brownie Points from completing adventures and achieving personal Goals. The standard list of Goals includes Sex, Wealth, Fame, Soulless Science, and Serving Humanity. Each player chooses one, or makes up his own.

The rules for ghosts are just as simple as those for players. The Operations Manual provides 12 ghostly powers, things like possess, animate, terrorize, and, of course, slime. A ghost also has ratings for Power (how many dice it rolls to do things), Ectopresence (how many hits it can take), and a Goal. A ghost’s Goal is perhaps even more important than a PC’s, because it can provide another way to get rid of the ghost besides blasting it (which doesn’t work on every ghost anyway). For example, the ghost of a struggling director might stop haunting his former movie studio if the Ghostbusters manage to finish his movie and arrange a screening.

Another important part of the game is the use of equipment cards. If your Ghostbuster has a PKE meter, ecto-visor, and ghost trap, then you’ll have cards in front of you to remind you of that. Some cards also contain rule info, such as the card for alpine gear telling you it adds three dice to your Muscles pool. (You may have guessed that not all the cards are designed to be serious, or actually useful.) The game even has cards for tomes such as Tobin’s Spirit Guide and Spates Catalog of Nameless Horrors.

Ghostbusters International

Three years later, in 1989, West End released a second edition of the game: Ghostbusters International, developed by Aaron Allston and Douglas Kaufman. The game’s release coincided with the second Ghostbusters movie, though nothing in this edition’s contents even hints at that fact other than the Ghostbusters 2 logo and a two-sentence mention of the film in the rulebook’s introduction.

Ghostbusters International (GBI) came in a box, like its older brother, and similarly shipped with rulebooks and 6 dice. This time, though, the main rules were put into a single book (plus a booklet of handouts). Another notable change was the absence of equipment cards and Ghostbuster ID cards from this edition. (Boo.)

The basic Ghostbusters system remained the same, though GBI was noticeably more complex. The added complexity wasn’t as great as the change between, say, original Dungeons & Dragons and 3rd Edition; it was more a case of adding auxiliary details, rather than changing the basics of the system. In other words, it still had 4 Traits and 4 Talents, used dice the same way (including the Ghost Die), and had Brownie Points and Goals. But in addition, it now had a full-page character sheet, with lines for physical description details, health status, wound effects, and where on the body each piece of gear is equipped.

Other key changes in this edition were a longer and more detailed equipment list, rules for differentiating physical ghosts from ethereal ones (and intelligent ghosts from mindless ones), encumbrance rules, ghostly weaknesses, greater vs lesser ghost powers, and supernatural abilities for humans. Also, for the first time, we have a full-page ghost character sheet.

I’ve encountered some Ghostbusters players and Ghostmasters who complained about the GBI edition, saying that the added level of detail was not an improvement, that the game should have remained as simple and unadorned as possible. Personally, I like both editions. I sometimes ignore the GBI additions, running my game exactly as it was in its first edition. On other occasions, I add some GBI detail, especially the expanded ghost rules. (Encumbrance rules, however, can go sit in the corner.)

Supplements

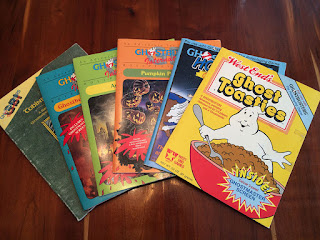

The game was supported by the release of eight supplementary books–three for the first edition and five for Ghostbusters International. The first edition books were all adventures: Ghost Toasties, Hot Rods of the Gods, and Scared Stiffs.

In Ghost Toasties, the players face a supermarket cereal killer, a demon-haunted school, and twisted cartoon cereal mascots living in Candyland. The cover of Ghost Toasties also serves as a handy three-panel Ghostmaster’s screen! Hot Rods of the Gods features juvenile delinquents from outer space, a demolition derby mini-boardgame, men in black, and a re-designed and alien-enhanced Ectomobile.

For Ghostbusters International, West End published four adventures and one sourcebook. The flagship adventure (in name, at least) was Ghostbusters II: The Adventure, which allowed YOUR Ghostbusters to save the world from Vigo the Carpathian while the original Ghostbusters are locked away in a psychiatric ward. (Like Ghost Toasties, this adventure came with a Ghostmaster’s screen, this one updated for GBI).

In ApoKERMIS Now!, the team faces an evil from the “Big Book of Dark Ceremonies and Party Games.” Pumpkin Patch Panic is a Halloween-themed adventure in which the bad guys want to make Halloween last forever. (Doesn’t sound bad to me!) And in Lurid Tales of Doom the PCs must accompany a reporter for a tabloid to look for evidence of the supernatural in the newspaper’s stories.

The only non-adventure sourcebook published for Ghostbusters was Tobin’s Spirit Guide, easily the beefiest of the Ghostbusters supplements (at 76 pages). The Guide is a sampling of ghosts from around the world. Some highlights include Egyptian gods, boggarts, a Gozerian cult, Baba Yaga, the Headless Hunter, voodoo loas, Old Tom the pirate, and the world’s first feminist. An appendix at the back of the book also provides a reference to ghosts featured in previous Ghostbusters adventures.

Legacy

1990 was the last year of Ghostbusters RPG releases. Even so, you can still find Ghostbusters games being run at conventions today, as I did at Gen Con the last two years. With a little luck, you can find a used copy for sale. (Every time I check eBay I see a few available.) Even out of print, this game lives on.

What’s more important than the game itself, though, is what it inspired. I believe that much of what’s great about gaming today can be traced back to Ghostbusters. It was the first system to use a dice pool, a concept that was the basis for West End’s next game, Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game. It was rules-light, and easy to teach to new players. Even the Ghost Die lived on in later games, appearing as a wild die, a drama die, and in a strange case of becoming your own grandparent, a computer die in the next version of Paranoia (which will also use equipment cards!).

As we noted earlier, Ghostbusters was the creation of both Chaosium (the Call of Cthulhu people) and West End Games (the Paranoia people), and that seems perfectly symbolic. Horror plus twisted humor. Solid rules plus a minimalist level of detail. Supernatural entities plus a quirky way to bounce dice. Other games inherited this thematic influence, too, and we’ll cover some of them in a future article.

Have you ever played the Ghostbusters RPG, or any other spook-hunting game? I’d love to hear your stories, memories, or possessed ramblings in the comments.